This essay was written after I attended the cinema première of The Smile’s Wall of Eyes, at EYE Amsterdam. You can read Daniël’s account of that same evening on his website.

On The Smile

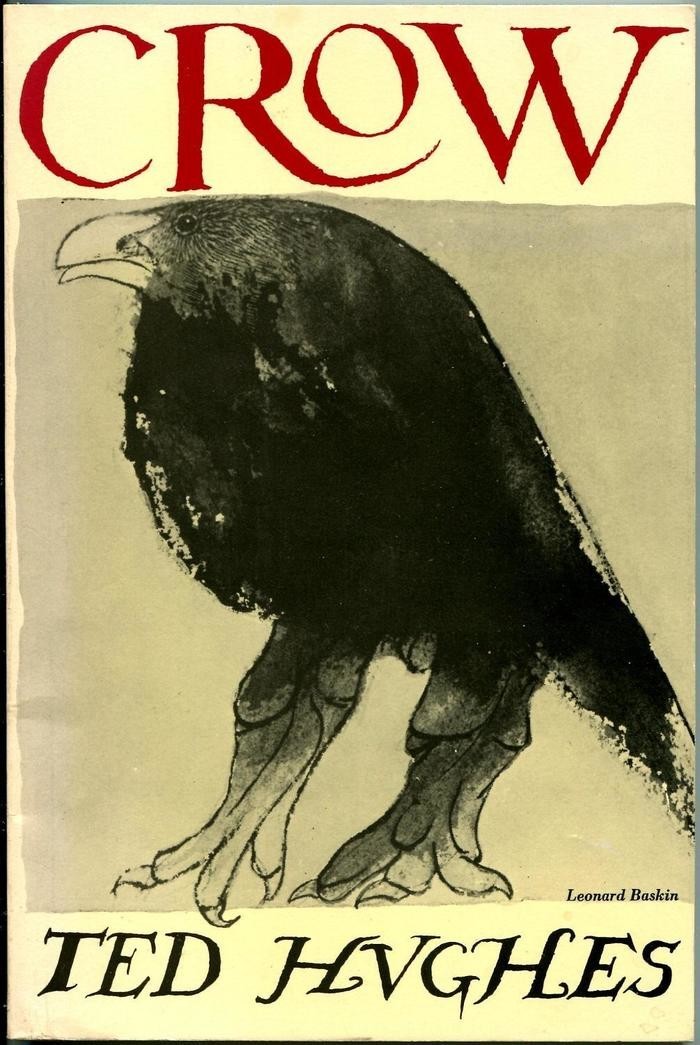

May 2021. Thom Yorke shares a photocopy of the second-half of Ted Hughes’s poem ‘The Smile’, announcing his latest project to his online following. Forming the heart of Crow (1970), a bleak collection of poems Hughes wrote in the barren period after the suicide of his estranged wife Sylvia Plath, ‘The Smile’ describes a force that runs through the earth’s skin and clouds, seeking a place to arrive for only a brief moment. It eventually does so in the widening eye of an ‘unlucky man’, whose soul seems to be lost. An unnamed crowd watches as the smile rises through the man’s ‘torn roots / Touching its lips, altering his eyes / And for a moment / Mending everything / Before it swept out and away across the earth’.

A few days later, Thom Yorke, Jonny Greenwood, and Tom Skinner play a set of six songs, as part of the lockdown version of Glastonbury. Thirteen minutes in, Yorke says: ‘Ladies and gentleman, we are called The Smile. Not the smile as in ‘ha-ha’, more the smile of the guy who lies to you everyday’. He smirks, the microphone echoes, the video distorts. Skinner’s drums kick in, followed by Greenwood’s deceptively groovy guitar riff. ‘What will now become of us?’ Yorke sings. Nobody knows, that much is clear. Dissonance is the only constant in the musical universe Yorke has built over the last three decades, and The Smile is no exception.

Crow with Red Sky (1983)

Crow with Red Sky (1983)Painting by Leonard Baskin (1922–2000).

January 2024. The Smile is about to release their second album Wall of Eyes on Friday. It’s Tuesday, and we have tickets to listen to the album in full before it comes out. There’s merch, but no band. I’m not sure what I’m hoping to find on the big screen, but here we are. Seated in our cinema chairs, we watch The Smile play in silence. Greenwood folds, Skinner sways, Yorke smiles. We smile with him, tentatively. Their songs start to take shape in our heads—the analogue synths, the layered vocals, the spacious percussion. What else will they have in store for us? We think we know this band, but all we know is what they have left behind for us. In these first inaudible eight minutes, a new landscape slowly comes into view. As the band leaves the recording studio, we get ready to follow their tracks. We sink deeper into our chairs, and let Wall of Eyes wash over us.

In an interview with Q Magazine in 1997, the year Radiohead’s OK Computer was released, Yorke said he wanted to build something up he could also watch fall apart, and to then find beauty in that fall, like Miles Davis did with Bitches Brew. This desire for the fall still shines through on Wall of Eyes. Yorke and Greenwood have never stopped chasing accidents in their respective projects, but over time, they have learned to appreciate the happy ones.

Where Radiohead albums like OK Computer, Kid A and A Moon Shaped Pool have given us perfect landings after sheer drops and high pinnacles, The Smile seems mostly invested in movement itself, in letting go of the wheel without knowing where you are, or where it ends. Playing with irregular time signatures, inimitable chord progressions and tempo changes that edge on the bizarre, this band clearly intends to defy our expectations of a forward trajectory, of a coherent narrative. Instead, they knock out oddly-shaped holes in the wall, so we can step into strange new places we didn’t know existed.

‘Wall of Eyes’ (2023)

Poster for music video, directed by Paul Thomas Anderson.

Ted Hughes once said that the poets he admired somehow ‘managed to grow up to a view of the unaccommodated universe’ with ‘all their sympathies intact’, showing ‘the simple animal courage of accepting the odds’. The Smile seems to have grown up to a similar view, showing us the same simple courage by going beyond the tide, not against. Their music is destabilising, but never destructive. It brings harmony to the wildest of places, and creates chaos in moments of calm. If this album is a map, it is meant to mislead, to let us travel in circuitous routes. It drifts, and we drift with it.

As the credits roll in, I know I will carry The Smile with me on nocturnal car drives and sunny bike rides, where it will, for brief moments in time, mend everything. And I will be here for it, long enough to see it drift off, again and again.

‘Crow’(1970)

Ted Hughes, Faber & Faber