This essay was rewritten and read as part of Seanchoíche, on the theme of “Belonging”, which took place on Nov 23, 2023 in Murmur. An earlier version of this text was written and presented during the Open Set Lab 2017, taking place at Beeld & Geluid, in Hilversum.

On Windows

“Vision itself has a history.”

— Heinrich Wölfflin, in ‘Principles of Art History’

It’s 1896. The French poet Charles Baudelaire publishes ‘Le Spleen de Paris’, containing a poem called ‘Les Fenêtres’, or ‘Windows’. In this poem, he describes how he sits in his apartment and looks out of his window.

“Looking from outside into an open window one never sees as much as when one looks through a closed window. There is nothing more profound, more mysterious, more pregnant, more insidious, more dazzling than a window lighted by a single candle.”

Across the ocean of roofs, he sees a woman who never leaves her house, her face already lined, her body forever bending over something. He looks at her gestures, her dress, her face, makes up her story, tells it to himself, and weeps.

“Perhaps you will say ‘Are you sure that your story is the real one?’”, Baudelaire ends the poem. “But what does it matter what reality is outside myself, so long as it has helped me to live, to feel that I am, and what I am?”

It’s 2023. I sit in my apartment, reading this poem. I decide to look out of my window. Across the street, I see a young man forever bending over something, blue lights flickering on his glasses, the stories of others flashing by behind the many windows that lay open in the palm of his hand.

I wonder if what he sees, this reality outside himself, helps him to live, to feel that he his, and what he is. I also wonder if he ever looks out of his window to see me forever bending over something, if he notices my gestures, my dress, my face, makes up my story, tells it to himself, and weeps.

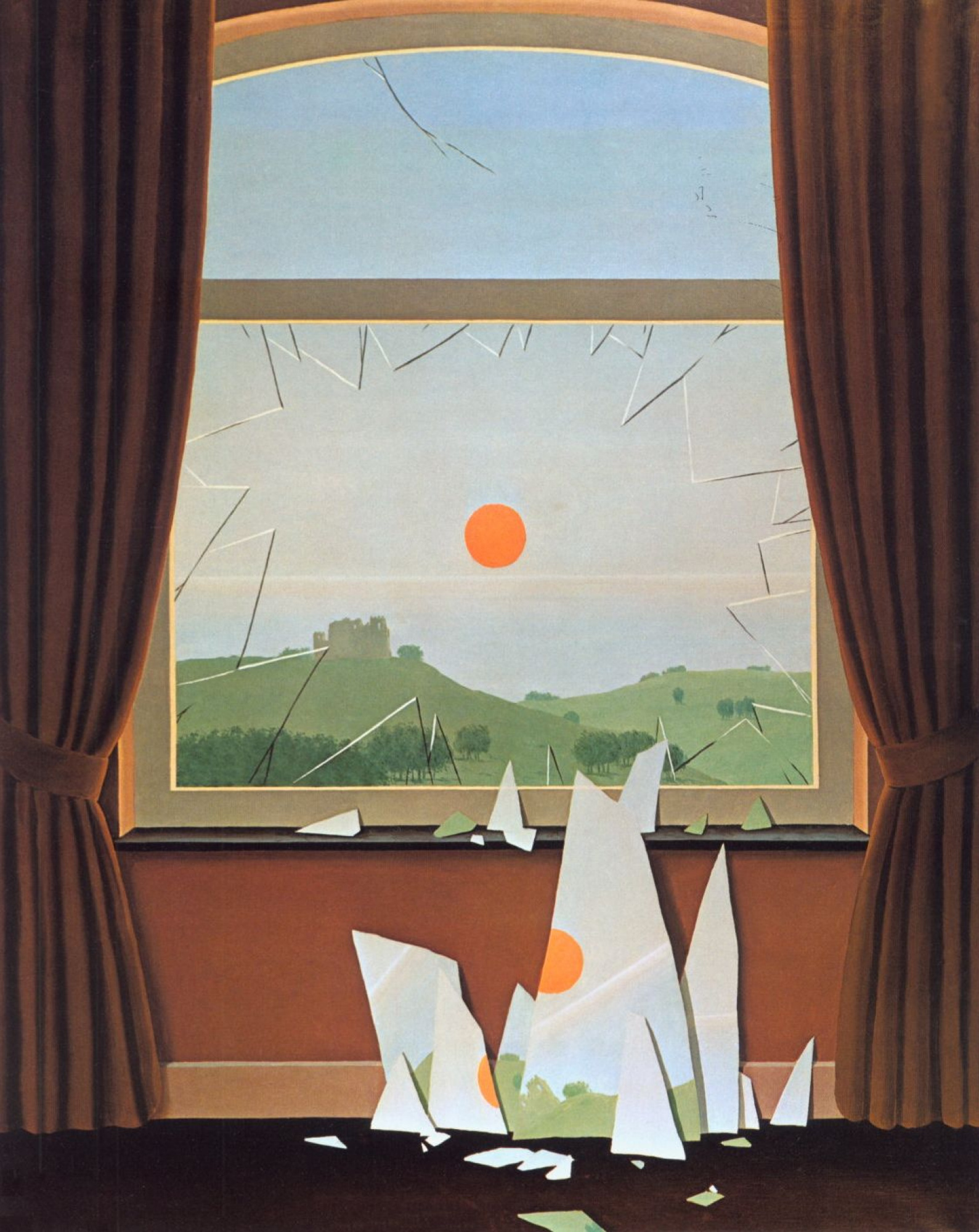

The woman Baudelaire sees through his window became a surface, on which he could project a life, a story of his own. Simultaneously piercing and reinforcing the barriers between him and her, that window was made of ghosts and reflections, rendering the everyday into a house of mirrors, in which the distinction between the inside and outside, the private and the public, the two- and three-dimensional, and the animate and inanimate, became impossible to trace.

The word ‘window’ stems from the Old Norse vindauga, which translates as vindr ‘wind’), and auga (‘eye’), describing both an opening for light and ventilation to pass through, and a protective shield to keep wind and cold out. But the window as described by Baudelaire cedes this purely architectural definition: his window not only opens and protects our view, but actively frames it, or holds our view in place.

Since Baudelaire strolled through the Parisian streets, windows have taken on many new forms. Elevators, escalators, cars, trams, trains, planes and rockets introduced new ways of seeing the world through a glass wall at a different pace and at a greater distance. These new means of transportation provided us with an unprecedented mobility that changed our view tremendously.

René Magritte, 1964

Looking out the window in the heavy darkness of the subway channels, for instance, I see my face mirrored in the window and, at the same time, see traces of other faces, all smudgy and ghostly, around me. Circling over the polders of Noord-Holland in a darkened plane, I look through the oval, double-layered glass and wonder how they ever managed to capture the wetlands into such a tight grid, and what that says about this place I call home.

While these new modes of transportation provided us with a new mobile visibility, mass media introduced a virtual mobility. Replacing the windscreen with a cinema screen, we no longer move our bodies. Here, the window itself is used to transport moving images to us. This experience does no longer rely upon our physical mobility, but upon the mobility of the gaze.

Sitting in front of the many screens that surround us, we have become immobile spectators that rely upon a mobility that is simulated for us. Screens that show us temporal worlds in which we do not really participate, but that have become so familiar to us, so intertwined with our own perception of reality, that we often forget to look outside our windows to see what's going on out there.

As an early component of the graphical user interface, the computer window referred not to the actual frame of the machine, but rather to a subset of its screen surface: a screen within a screen, a window within a window, layered on top of each other. This multiplicity enables us to see everything, everywhere, all at once.

It is this multiplicity that my neighbour holds in his hand as I watch him. A reality that is filled with things and voices and stories. Stories that are laid out as a Cubist painting, made out of frontal views, a suppression of depth, and overlapping layers. And yet, it's these stories that can make us feel like we belong to people and places far from here, and alienate us from those around us.

In the intro of his poem on Windows Baudelaire writes:

“What one can see out in the sunlight is always less interesting than what goes on behind a windowpane. In that black or luminous square life lives, life dreams, life suffers.”

From Giphy

We know the world by what we see: through a window, in a frame, on a screen. It is through these luminous squares that we experience not one but many imitations of life, with only a simple swap of our thumbs. As we spend more of our time experiencing the world through these windows — how the world is framed may be as important as what is contained within that frame.

Tonight, I’m standing before you in the (metaphorical) sunlight, meaning, not behind a window. I’m looking you all directly in the eye, as you're looking at me.

Maybe bits and pieces of what I’m saying here will show up somewhere, on someone's screen, making it all seem much more interesting than it was. But the most important part for me is that I’m here, listening to the stories that are being told here tonight, hearing how others view the world around them, how they see and are connected to other people, to other places, smells, memories, systems.

Without projection, I know this will help me live, make me feel that I am, and what I am. Not by making up stories about others, but through the stories they tell me about themselves.

As Joan Didion so famously wrote: we write stories in order to live. And I’m so happy that a place like this exists, where, for a brief moment in time, this ‘we’, a group of people who are mostly unfamiliar to me, are here together, listening to the same thing, at the same time, before we go back to being dazzled by the many layered and fragmented windows that demand our attention.

Thank you.

From Giphy